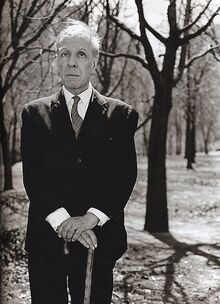

In 1976 and 1980, Jorge Luis Borges gave two interviews for the Spanish TV show A Fondo (English: "Thoroughly") hosted by journalist Joaquín Soler Serrano. The talk show was famous in the late 1970s for its interviews of several art, literature, and sciences celebrities.

Some of the guests that appeared on A Fondo are Julio Cortázar, Salvador Dalí, Roman Polanski, Bernardo Bertolucci, Yehudi Menuhin, Manuel Puig, among others.

Translation Notes[]

The translation of the one and half-hour interview was done by me, a friendly anon from Argentina. As English is not my first language you'll probably find some grammar mistakes and words that sound a bit artificial. Spanish is also a difficult language to translate from as its grammar differs a good deal from English. Plus, Borges was 77 years at the time and some portions of the dialogue were inaudible.

I've chosen to do the most literal, yet readable, translation possible as Borges is known for his phrasing and selection of words and only the rambling questions of the host were slightly simplified.

Original book titles are formatted in italics with the English translation between brackets and quotation marks. Most of the poem translations were taken from the Internet and were done by professional translators.

Almost every reference and translation note can be found at the bottom of this page and some short notes are simply displayed between brackets in-line with the rest of the text for an easier read. Author names and other important figures link to their respective Wikipedia entries.

Even though I proofed this translation a couple of times, feel free to edit this page if you find any weird or broken English phrasing.

You can mail me at: anon.of.miyamoto(at)gmail.com if you feel like it.

The Interview[]

Part 1[]

Joaquín Soler Serrano (Host): Today we are happy to have achieved what has been one of our goals since the beginning of this show, which was to have Maestro Jorge Luis Borges honoring us and filling our spirit with joy. El Maestro Borges, has honored us coming from Argentina to chat with us for a long time. He has imposed no conditions. He has asked us to spur him and to harass him. Maestro, we are willing to harass you lovingly—

Jorge Luis Borges: Why, heh... I'm very timid, so I hope there's I can be worthy of your time...

Serrano: I'm absolutely sure that everything you say will be of great interest to our audience.

Borges: I'll do my best.

Serrano: You have many friends and fans here—

Borges: Yes.

Serrano: People that know you for your work—

Borges: Spain is very generous.

Serrano: But they have never seen you in person, heard your voice, or known, directly from you, your opinion on so many things. You are a living monument… of intelligence... You are a man who's been said to be all brains, but I think that's an exaggeration.

Borges: I think so too, heh.

Serrano: Not because your mind is not a mind is not of genius and cosmic proportions, but because you also are a living body. And as such, you are a sensitive being. You've been accused of being a cold man—

Borges: No, that is not true. I'm... unpleasantly sentimental. I'm very sensitive. When I write, of course, I try to, well, to have a certain pudency. And as I write through symbols and I never openly confess, people think this algebra means... coldness. But it's not like that. It's the complete opposite. This algebra is a form of pudency... and emotion, of course.

Serrano: I think that turning feelings into mathematics is something very complex and very beautiful.

Borges: That's the task of Art. It is to transform whatever happens to us into symbols, to transform it into music, to transform it into something that may last in the memory of men. As artists, that is our duty. We must comply with it. Or else we'd feel very unhappy.

Serrano: We could then say that feelings and sensibility are primitive, basic things, that are given to human beings in the very act of birth, of existence.

Borges: Yes, but in the case of the writer, or in the case of every artist, we have the duty, for the most part, happy duty, of transforming everything into symbols. Those symbols can be colors, shapes, sounds. In the case of the poet, they are sounds but also words... Also fables, tales, poems. What I mean is that the work of the poet is endless. It's not about working from one hour to another. You are constantly receiving something from the outer world. It all has to be transformed; it eventually has to be changed. And in any moment a revelation may come. That is to say, that the poet never rests. He is working constantly, when he dreams too.

In my last book, La Moneda de Hierro ("The Iron Coin"), there's a poem I composed while dreaming. It's not worth much, but... well, it provides a psychological curiosity.

Serrano: That capacity of composing poems even in world of dreams must be incredible. How did you feel when you found yourself with that dreamed poem? It was like a different finding, yes?

Borges: Well, I dictated it the following day. I didn't know if it had any value or not. And after some days, I asked to re-read it and I found out that, well, it was seemly poem and that it could be published... especially after explaining that it was a gift from a dream. I thought of Coleridge, who dreamed the poem Kubla Khan, the entire poem, and while he was dreaming, he heard a music. He saw that very same music building a palace... and he also heard the poem. A long poem, it's extraordinary. In my case, no, it's a short poem without other value that being a psychological curiosity. A gift of the dream. Possibly, a Greek present. Possibly it's not worth much. But in any case, I published it with all the others, and nobody noticed that it was any different from them.

Serrano: The poet—

Borges: I think I changed one word.

Serrano: Yes?

Borges: Yes, only one. Now I don't remember which one, but I know that something had to be changed because the dream had made a mistake. In the end, my vigil mind was better than the dream mind, yes.

Serrano: So you believe that even in dreams, mistakes can be made.

Borges: Yes. And also while awake (he laughs), no matter how strange it may sound. In the vigil, more so, without any difficulty.

Serrano: Maestro, you like to say you've made every possible mistake.

Borges: I think that yes. And eventually, after 77 years, I've found some successes. Every mistake should have to be discarded, of course. And I've repeated many, naturally.

Serrano: So you mean that making mistakes is necessary?

Borges: Yes, I think it is necessary. And possibly, if I ever reached the age of 200, I could have learned something about the craft of writing. I'm still learning.

Serrano: What distance do you see, speaking of these things of evolution and transformation, between the Borges of 20 years ago and the Borges of today?

Borges: I think that, essentially, we are the same. But, the Borges of today learned some cunnings, learned some skills... and something about modesty too. But I think that, essentially, I am who I was when I published my first book, Fervor of Buenos Aires in 1923. And I think that in it, everything I would have done later is laid out. Except it is between the lines, and only for myself. It's like a secret writing, that lays between the lines of the public writing. And I think there's everything, except that nobody can see it but me. I mean that what I've done afterwards, it's been to re-write that first book, which was of no great value, but with time it expanded itself, branched itself, enriched itself. And I think that now, well, I can finally boast of having written a few valid pages, a so-so poem; and what else could a writer want? Because to breathe out a whole book is too much already.

Serrano: Those figures, those keys, those secret codes, that secrecy... do you care to share it with someone? You don't write for yourself alone, or do you also write for others to understand, to decipher, to unravel?

Borges: No, because once something has been written it's beyond me. When I write, I do it urged by an intimate necessity. I don't have in mind an exclusive public, or a public of multitudes, I don't think in either thing. I think about expressing what I want to say. I try to do it in the simplest way possible. Not at first; when I began writing, I was a young baroque like all youths are, on account of shyness. The young writer knows that what he says has little value so he wants to hide it, mimicking a writer of the 17th Century or a writer of the 20th Century. Now, instead, I don't think about the 17th or the 20th centuries. I try to simply express what I want and I try to do it with common words. Because only the words that belong to the spoken language are effective. It's a mistake to assume that all the words in the dictionary can be used. There's many that can't.

For example, in a dictionary, you see as synonyms the words "bluish", "cerulean" and "azureous", and some other word too. The truth is that they are not synonyms. The word "bluish" can be used, because the reader accepts it, so to speak. But if I put "azureous", or if I put "cerulean", no, they are words that point to different or opposite directions. So, actually, the only word that can be used is "bluish", because it's a common word that glides along the others.[1]

Serrano: So the other words would sound artificial.

Borges: So if I were to put "cerulean", it's a decorative word. It's as if I suddenly placed a blue spot in the page. So I believe it's not a permissible word. It is a mistake to write with the dictionary. One has to write, I believe, with the language of the conversations, of one's intimacy.

Serrano: But that can be reached with the passing of time, with the incantation?

Borges: Yes, it comes with time. Yes, because it's very difficult for a young writer to resign and write with common words. And possibly, there may be some words that are common to me but not to others. Of course, there's that mistake. Because every human group has its own dialect. Each family has its own dialect. Possibly, there may be words that are common to me and not to others, but anyway...

Serrano: But there are, there have been, there will be writers, mature writers, some even with Nobel's, that write with that Baroque-ism, with that rhetorical thing, full of metaphors—

Borges: But I think that's a mistake. I think that the Baroque style stands between the writer and the reader. It could also be said that the Baroque style has a sin, the sin of vanity. If a writer is baroque, it's as if he was asking to be admired. Baroque art feels as an exercise of vanity. Always. Even in the case of the great ones. I speak about John Donne, Quevedo. What I mean is that it feels like an exercise of vanity, like an arrogance of the writer.

Serrano: There's something like a plea. A plea is being asked to the reader.

Borges: Yes, yes, yes. That phrase of yours is better. Yes, like a plea. And sometimes a tribute is demanded, which is even worse. Both things are unpleasant.

Serrano: What's been said (in Spain), and perhaps that is why, that accusation of coldness—

Borges: But it's entirely untrue. People that know me can tell I'm not like that.

Serrano: Perhaps it's the conciseness, the precision, the strictness, which I believe is the most desirable, and the hardest thing to achieve—

Borges: Well, my master, I still call him master, although I know I will never write like him, Rafael Cansinos Assens, spoke once about my "numismatic" style. It's a lovely phrase, if only I could make coins...

Serrano: Well, I have some clippings here of some of Cansinos Assens remarks about you—

Borges: Oh, well, no doubt he's been very generous with me and probably there we'll find the "numismatic" remark—

Serrano: He says "Borges passed between us like a new Grimm, full of discrete, smiling serenity (...)". You've always been a great discreet.

Borges: I could only hope so (he laughs).

Serrano: "(…) fine, even-tempered, with the head of a poet, held back with a fortunate intellectual frigidity", Cansinos said, "with a classical culture of Greek philosophers and Oriental troubadours for his liking of the past, forcing him to love calepino's (Latin dictionaries), folios and underminer of the modern wonders".

Borges: That's fine, it's Cansinos' style. His musical style.

Serrano: There's that world of yours, somewhat enigmatic—

Borges: Yes, "underminer of modern wonders." There's the iteration, eh?

Serrano: You met Cansinos on your first stay in Spain.

Borges: Yes.

Serrano: Which was around the 20's.

Borges: Around the 20's, I don't remember the date. The truth is I remember a lot of things but not dates.

Serrano: I have some dates here, and with your help we'll remember them together. Let's go back to Buenos Aires, to August 24th, 1899—

Borges: Alright.

Serrano: The day Jorge Luis Borges Acevedo enters this world.

Borges: So they told me. Well... (he laughs)

Serrano: They've told you all this?

Borges: Yes, all that. So, possibly, none of it actually happened.

Serrano: You were the son of Don Jorge Borges Haslam, and of Leonor Acevedo—

Borges: Leonor Acevedo.

Serrano: And you came from an old Argentine family, pioneers of Independence.

Borges: Yes, I'll tell you more as I can go further. I'm the descendant of a certain mister, Juan de Garay, who founded the city of Buenos Aires. And of somebody else, Jerónimo de Cabrera, Andalusian, who founded the city of Cordoba. [2] I'm the descendant of conquerors, Spanish conquerors, and as of late, of Argentine soldiers who fought against the Spaniards, which in the end was the natural thing to happen. And then of warriors of Uruguay. Mine was a family of warriors. On my English grandmother's side… hers was a family of Protestant pastors, which is fine with me, because it means I carry the Bible in my blood.

Serrano: In this lineage of warriors, your father was a notable exception.

Borges: Yes, it was an exception due to his myopia. But my grandfather, Col. Francisco Borges, died in 1874 in the combat of La Verde. After the battle, he had himself killed deliberately. He wanted to die for I don't know what political circumstances. General Mitre had already surrendered, and he (his grandfather), rode on horseback, a white dappled horse; he wore a white poncho, and moved forward, not galloping but trotting, offering himself as a nice shot for the sharpshooters of the enemy army; he received two bullets and was killed.[3] But the problem was that Remington rifles were first used in that battle. So, it appears, the bullets that killed him had a new sound to them.[4]

Serrano: However, what's surprising about you is that, well, being the heir of all those bloodlines, of that war dynasty, you are more of a skeptic man regarding this subject.

Borges: It is true. But I've probably been wrong for a long time. Because I believe the Arms are a honorable exercise. Never mind exercising them for such and such cause. Being a soldier is something noble. I know that by saying this I make a lot of enemies, but I don't try to befriend or ingratiate myself with nobody. Besides, you have to think poetry starts with the epic, doesn't it? The epic is the first expression of poetry. In every culture of the world. It always begins with the Arms and men. And that happens always.

Serrano: You've always been a person of great independence. You always speak your mind.

Borges: Well, I try do so. And that's why I'm frequently indiscreet. Today, for example, I'm speaking with complete sincerity.

Serrano: And we thank you for it, Maestro. Now, let's go back. We left at your father, being a peaceful English professor.

Borges: Yes, but he was also an individualistic anarchist, a Spencer reader too. Disbelieved in the government, in all governments in general. Actually, he was a Psychology professor.

Serrano: He was also a Romantic poet.

Borges: Yes, he was also a poet. And he left some good sonnets. But he wanted that I would have the destiny that didn't happen to him. The destiny of a writer. I knew since I was a kid that my destiny would be a literary destiny. It was indicated to me since I was a kid, tacitly, which is the only way to appoint things. To take them for granted. And ever since childhood I knew mine was going to be a literary life. And my father gave me free run of his library. A library of, mostly, English books, and I was educated in that library. I remember, between books, a Garnier edition of Don Quixote. I read and re-read that edition. And many years later, when I returned to Buenos Aires, I wanted to re-read Don Quixote in the same edition, which was very hard for me to find, with the same steel engravings, because I thought that was THE Don Quixote edition, being the first one I ever read. I've spent my whole life reading, and I have a good memory for verses, and even a little time for a few pages in prose too.

Serrano: Your sister, Norah, has said on several occasions that she remembers you being a child, lying face down reading all the time.

Borges: That's true. It's an exact memory. I don't know if—

Serrano: And did you read everything that fell on your lap? Or did you have a capacity of selection—

Borges: No, I remember I was a hedonic reader. I read what I liked. And since my father never made me read anything in particular, he never told me, for instance, "This is Don Quixote and it's a masterpiece". No, he would let me open the book and read it. And he never discussed literature with me.

Part 2[]

Serrano: Do you remember what impression did Don Quixote leave you? Your encounter with this work.

Borges: Well, at first, it was a paradox. Because what I admired in Don Quixote was what Cervantes loved, yet it was precisely what he attacked. The world of chivalry. For me, Don Quixote, was a novel of chivalry. And in a certain aspect, it is one. Because, without a doubt, Cervantes feels no sympathy for the priest, for the barber, for the bachelor, for the Dukes. He feels sympathy for Alonso Quixano. Besides, in some ways he is Quixano and not the others. What a strange book, a very strange book.

Serrano: Yes, don't you think that it cannot be categorically affirmed that he wanted to make a parody of the book of chivalry?

Borges: No, I don't think so. Gurza has noted that by the time Cervantes published Don Quixote, those books were not read so much, that perhaps Cervantes was the only remaining reader of those books. And that he liked them very much. But Cervantes noted that there was something absurd in those books, and so he wanted to cure himself from that passion.

Serrano: And as a writer, what do you think of Don Miguel?

Borges: Well, I had a conversation with Ernesto Sábato. Sábato told me something that I find very right. He says, "It's always said that Cervantes wrote poorly, just as it's always been said that Dostoyevsky wrote poorly. But if that poor writing served them to leave us Don Quixote and Crime and Punishment, so to speak, or Stepanchikovo (The village of…), they didn't write so badly." They wrote what was necessary to meet their ends. It is Sábato's opinion, but I think that... we can't censor what Cervantes wrote from a rhetorical point of view. Of course, Quevedo, could have corrected any page of Cervantes', Don Diego de Saavedra Fajardo too, Lope de Vega as well. But they couldn't have written it. It's easy to correct a page, but to writing it is very hard. They wouldn't have been able to write the entire oeuvre.

Serrano: Anyways, didn't you preferred Quevedo?

Borges: Yes, but I think I was wrong. I think I prefer Cervantes now and, I'm going to be blasphemous now... because I feel something, in the end... I've admired Quevedo a lot, I do admire him, but, he's only an admirable object, only an admirable thing. Instead, Cervantes and Alonso Quixano, who wanted to be Don Quixote and whom he was, they are personal friends of mine. It's something else. It's a friendship that is never established with Quevedo. Nobody befriends Quevedo. One can admire him—

Serrano: We went offtrack, to Don Quixote—

Borges: It's true, it's been so long since we left that library.

Serrano: Strolling through your father's library in your childhood. Those years, I imagine, were filled with fantasy and richness, because every day you peeked into a new world.

Borges: Yes, I read a lot. And I didn't know they were renowned books. For example, I read a book, published only a few years before, The First Men in the Moon, by Wells. I also used to read Kipling, Stevenson. I read Arabian Nights. Capital books for me. And I also read awful books. But of course, a child does not compare one book with another. A child accepts what he reads. And he does so with gratitude. So I didn't really think that Don Quixote was better than Juan Moreira, or that it was better than Hormiga Blanca (“White Ant”) by Eduardo Bustero. I used to read both books and I felt pleased. I didn't think they were any better or worse. I didn't judge critically. I simply enjoyed books. Perhaps, I was wiser back then, when I simply enjoyed them, than now when I try to judge them.[5]

Serrano: Well, but not only did you enjoyed them, you were also enriching your internal wealth, fed by all those books. The world of Borges was growing.

Borges: Yes, but I couldn't have known that.

Serrano: Before you were 10 years old, you had already written.

Borges: Yes, abhorrently.

Serrano: I don't think so.

Borges: I wrote in Old Spanish, there's nothing else to say (he laughs).

Serrano: By the age of 10, in the newspaper El País (“The Country”)—

Borges: Yes, a translation of The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde. And I think it was pretty good. I haven't looked at it ever since.

Serrano: So it wasn't so abhorrent.

Borges: No. But well, I think that Oscar Wilde is the easiest writer. People that begin studying English start with Oscar Wilde. With German it is Heine, which means mine was no great feat.

Serrano: On the other hand, not only did your father spoke English, you had an English governess.

Borges: Yes, but she wasn't so important. Because I also had my grandmother who was English. She knew the Bible by heart. You could quote any given passage and she would say, book of Job, such chapter and such verse, and she'd go on. The Bible was written in Old English, the English of the Bishops, of the 17th Century.

Serrano: Apparently, your parents were afraid of all the contagious diseases of the time so it took you quite a long time to leave your home, which was why you spent so much time reading…

Borges: It's true.

Serrano: Which is why you had that governess, Miss Tink.

Borges: Yes, Miss Tink. And I think a cousin of hers was a famous malevo (a thug). Tink, the Englishman, a well-known daggerist[6]. How odd, Juan Tink. Like a tango with corte y quebrada[7]

Serrano: And how was she? Your governess.

Borges: I don't remember her much. I do remember my grandmother. I remember that when she was close to her death, we were all very sad and she asked for us. She was an old woman then, very fragile but also strong, like my mother. And she said to us: "There's no interest whatsoever to what's happening; I'm a very old woman, who's dying too slowly, this cannot worry or interest anybody".

Serrano: This happened some years after, in Geneva I think.

Borges: No, that was my other grandmother. No, this one died in Buenos Aires. However, how grand that she could foresee her own death, from far away, "a very old woman, who's dying too slowly". "An old woman who's dying very very slowly, that's all" (In English). That's all. Nevertheless, the house was in uproar.

Serrano: Those have been some of your obsessions, and also your intellectual concerns. Life and death, infinity, mortality, the serenity…

Borges: Excuse me, can I be indiscreet? Can I speak of the death of my other grandmother?

Serrano: Yes, sir.

Borges: Well, she was dying in Geneva. I never heard her curse. She spoke in a whisper. She was the daughter of Col. Suarez, who lead the front in the battle of Junín, in Peru. She was dying and we were all around her. She said: "Let me die in peace", and the bad word followed, which I had never heard before (he laughs). And she could only speak in a whisper. We felt she was a very brave woman. My father said, "The daughter of Col. Suarez sure is OK".

Serrano: And this anecdote, what could it clarify as far as your obsessions, life and death, of what's endless and infinite?

Borges: I don't know. Perhaps I did wrong in telling it, but I spoke from the heart and with respect.

Serrano: I know, Maestro.

Borges: I told it with reverence for her.

Serrano: What I'm asking is if it affected your concerns.

Borges: Possibly. Having witnessed those death-throes, and my father's, a very long suffering; like I wrote in a poem, he died "blind and smiling"[8]; and the death-throe of my mother, also very long; I was certainly marked by those things. But death has an effect on everybody. Death marks all men. The idea that we can cease to exist in any moment, that we are accidental, has to move everyone who's not insensitive.

Serrano: Your father's blindness was also premature. Around what age did he start—

Borges: Hmm, yes, I'd have to calculate it and I'm no good at math. If perhaps you could do it…

Serrano: Why, if you are THE mathematician—

Borges: He was born in the 1874, and he died in the 1938. Can you estimate how long he lived?

Serrano: If you're willing, we can do it. (Serrano starts writing on a piece of paper)

Borges: I'd need a computer, or something like that to do it myself.

Serrano: That is 64 years.

Borges: Much younger than I am. Of course, I always imagine him as a grown man, it's only natural.

Serrano: That is logical, you are seeing him as if you were a child.

Borges: I have committed the indiscretion of continuing to live (he laughs).

Serrano: No, you've done right to continue living. And I hope for many years to come.

Borges: Well, a long time, I don't know. A few more years, yes. I'd like to finish some of my works. There's some fantastic tales, there's a book regarding Scandinavian literature, there are some poems I'd like to write. I'm always asking a few months extension.

Serrano: Let's hope there will be many more months, Maestro.

Borges: We'll see (he laughs).

Serrano: We were speaking about an essay on Greek mythology you wrote—

Borges: I was plagiarizing the Classic Dictionary, but well, I called it an essay…

Serrano: That influence Don Quixote had on you, developed into something you wrote.

Borges: Yes, it was called La visera fatal ("The fatal visor"). What a shame.

(Laughs)

Borges: We can't help it.

Serrano: Then there was the translation of The Happy Prince, age 10, which was published in 1909 in El País… and in 1914, your first trip overseas, which I believe was vital—

Borges: Yes, to Europe, to Switzerland. The discovery of Europe. And then the discovery of Switzerland, a country I love a great deal but many people loathes and I don't know why. Because it's one of the most civilized countries on Earth.

Serrano: Switzerland was like a safe haven in the middle of the Great War.

Borges: Yes, Switzerland is indeed an admirable country. A country of Germans, of French, of Italians, who chose to forget their differences, who chose to be Swiss, to become something else. A country that never wanted to become an Empire. A country that's not nationalist because there's no plausible cult for a Swiss race made of Germans, French and Italians who stay together in an amicable fashion.

Serrano: In Switzerland you experienced your first encounter with the German language.

Borges: Yes, but it happened because I had read a lot of Hume, and from Hume I moved to Schopenhauer, and I read it English and I thought it would be beautiful to read the original text. So I taught myself German for my own purposes. I remembered Spencer who said that the teaching of grammar is awful, as well as teaching the philosophy of a language, that it's not necessary to study them, that it can be studied later. Besides, no child learns his own language through grammar. So I bought a copy of Tragödien nebst einem lyrischen Intermezzo ("Tragedies with a Lyrical Intermezzo") by Heine, and a German-English dictionary, English because it was the closest language to German I could think of. And so, I started reading. And after a while I realized I understood what I was reading and also enjoyed from an admirable poetry. Later I managed to read Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung ("The World as Will and Representation") by Schopenhauer in German and understood it entirely.

Serrano: And later on you translated some works from German—

Borges: Yes, I translated some—

Serrano: Some of them, even in Spain.

Borges: Yes, in Cosmópolis (a Spanish magazine), who's editor was Ernesto Gomez Carrillo. I translated a few. I mean, German is one of the languages I conquered which makes me feel proud. Because I learned the other languages due to different circumstances given to me. I learned French because I lived in Geneva. Now, Latin is a language I love very much but I've forgotten. It is a language that's easily forgotten. It's a pity. And English and Spanish were the languages of my childhood. Spanish comes first because I'm certain I'll say my last words in Spanish, not in English (he laughs).

Serrano: However, German was a personal effort, a calling.

Borges: Yes, which is what happened with Anglo-Saxon, or Old English. I resolved to study it and now I know a little. And recently I started learning Old Scandinavian, the Old Icelandic.

Serrano: You have a prodigious memory, can you remember your own verses

Borges: Yes.

Serrano: And the verses written by others, too?

Borges: Yes, the others', sure (he winks). I have good taste.

Serrano: The verses of Heine also?

Borges: Yes. How could I not remember Heine?

Serrano: Can you show us a little?

Borges: In German?

Serrano: Yes, please.

Borges: Well, but what I'm going to recite is very basic, a very South American pronunciation…

Serrano: There are many who speak German who will enjoy listening to you.

Borges:

- Ich hatte einst ein schönes Vaterland.

Der Eichenbaum

Wuchs dort so hoch, die Veilchen nickten sanft.

Es war ein Traum.

Das küßte mich auf deutsch und sprach auf deutsch

(Man glaubt es kaum Wie gut es klang) das Wort: "Ich liebe dich!"

Es war ein Traum.[9]

German has such music, and at the same time, open vowels like in Spanish, because in English there are no vowels, only mid-vowel sounds, especially in modern English…

Serrano: You are a sort of explorer, a constant explorer of cultures. What opinion do you have on the German culture? Of German literature in particular.

Borges: Perhaps I'm a little unorthodox. Because I don't look up to Goethe as I should, I don't admire Goethe's Faust. But I do admire his Römische Elegien ("Roman Elegies"). I mean, I'm not a superstitious reader. I know I should say Faust is a masterpiece, but not really… I consider it a mistake of his. On the other hand, I think of his Roman Elegies, and Goethe the man, and I feel a certain affection, and perhaps I can even understand his mistakes. The German culture is so rich, and I like the German language very much.

Serrano: But what we like about you, Maestro, are your own opinions, don't tell us about the common saying of everyone else; tell us your truth.

Borges: But what else could I possibly do…

Serrano: That is the value we thank you for so much… and regarding French culture, what is it that interests you?

Borges: Well, I think that the French culture is one of the richest. The proof is that if you take any other literature, that specific literature could be encoded in only one man. Of course you'd be making an evident mistake. For example, you can say Spain and think of Cervantes; England and Shakespeare; Germany and Goethe; but you cannot say France and name one single person. Because there are many names. For instance, if you were to say, France and Hugo, it would obviously be a false statement. If you were to say, France and Voltaire, much would be missing. La Chanson de Roland ("The Song of Roland"), much would be missing too. Or France and Verlaine, for example. Or even France and Flaubert. It's extraordinary. I don't like the French language, but I know I should, because it would be the instrument for approaching such splendid literature.

Serrano: Why is it that you don't like French?

Borges: It's the sounds. I remember what Schopenhauer used to say, that French is Italian spoken by a person with a cold. (Laughs) The nasal sounds of French.

Serrano: However, I know you spent—

Borges: It's only Schopenhauer's joke. I could never say that. I have no right to repeat it. I'm nobody to say such a thing.

Serrano: Because you are not Schopenhauer, above all. (Laughs)

Borges: No, I am not Schopenhauer.

Serrano: You are Borges.

Borges: It can't be helped (he laughs).

Serrano: However, you spent years submerged in the poetry of Mallarmé, you love—

Borges: No, but precisely, at that time, as I was studying in French, I was also discovering the German literature and language. I was also reading a lot of Joseph Conrad and Kipling. I also read Whitman, in English. What I found remarkable about French literature came later.

Serrano: You wrote a lot about Walt Whitman. Perhaps any essays we might know about…

Borges: Yes, I gave several conferences about him in the United States, about the extraordinary experiment of his. The idea was to write an epic of democracy. I mean, an epic without a main character, but where everyone was a main character. A democratic idea. And there's Walt Whitman as a character. Who's partially him, a portion of him or his projection, but there's also the reader, and every future reader. The Walt Whitman character in Leaves of Grass is a very strange character. Because the character is not the journalist who wrote the poem, he is many people simultaneously. He is the author, his projection and each reader. In the book he speaks of a Walt Whitman on several occasions. He says "What do you see, Walt Whitman", "What do you hear, Walt Whitman". He's talking about the reader. I mean, each and every one of us, when reading Leaves of Grass, becomes a character of Walt Whitman. It's a very curious experiment. Perhaps the most remarkable ever done in the history of literature. And by a great poet too.

Part 3[]

Serrano: What's your position on democracy?

Borges: What I wrote in the prologue of my last book, it's abuse of statistics, nothing more.

Serrano: You don't believe in democracy?

Borges: No. But, I may be talking as an Argentine. I don't believe in an Argentinian democracy. But perhaps democracy can be possible in other countries. And there are democracies, of course, in many countries. But in those countries, it doesn't matter if there is a democracy or something else.

Serrano: What could be a solution, now that you are speaking about the political problems of Argentina—

Borges: I have no solution. I'm not a politician.

Serrano: But as an observer…

Borges: For the time being, my only observation as to what could be convenient would be to delay the next elections about… 300 or 400 years, but beyond that, I can't think of any solution. To have a strong government, and a just government too. A government of Sirs and not of thugs. That's all I can say.

Serrano: During the years of Peronism, you were persecuted viciously. Your mother was incarcerated, your sister, your nephew too. You were dismissed from your position[10].

Borges: Well, yes. But it was such a modest position.

Serrano: It was a modest position, right?

Borges: Yes, but even so, they thought it was too important for me. But I have a clear conscience regarding Politics. Even though I don't understand Politics, I believe I understand Ethics. I know Peron's was a dishonest government. It was a very cruel and arbitrary government too.

Serrano: It appears some of your sayings about Chile's government had also been controversial.

Borges: Yes, but I don't know why they were surprising. It's only natural, given my age, for me to lean towards the right.

Serrano: Only because of biological reasons?

Borges: It's possible. And possibly I can't defend my way of action…

Serrano: You once inherited your father's anarchism? And believed in it while you were young?

Borges: Yes, and I believe it could lead to a good future. I can only hope we'll need no governments in the future, nor the need of countries.

Serrano: That would be the ideal?

Borges: Yes, that would be ideal. Or a minimum of government, or a municipal government like Spencer's. But of course, my thoughts regarding Politics should be disregarded. I know nothing of such things.

Serrano: Let's go back to literature then.

Borges: Yes, I can feel a little more confident in that area. If only I could feel secure in any area.

Serrano: Conversations always go from one place to another.

Borges: Yes, of course. They wouldn't be a living thing otherwise. They have to branch out.

Serrano: So, going back to what you said about cultures in general, we've examined your passion for German culture—

Borges: Well, I've been interested in many cultures. Chinese culture also interested me for some time, for example, Indostan philosophy (South Asia); I felt great interest for many things. Scandinavian mythology, Scandinavian literature more recently…

Serrano: What could you tell us about it?

Borges: Well, as I wrote in a poem not yet published, I could tell you that in Iceland, Germania's memory is salvaged, I mean, the memory of Germany, England, Netherlands, Norse countries… everything we call Germanic or Scandinavian mythology, really. The mythos of Ragnarök can be found in Iceland, all thanks to its people. I mean, Wagner couldn't have executed his work, William Morris neither, without men like Snorri Sturluson among other Scandinavians who saved all their history. We would have lost it. What would we have if it wasn't for the Scandinavians? We would only be left with "Thursday" (in English), day of Thor; "Wednesday", day of Wōden; and that would be all. But what about the myths? The entire story of Baldr, of Ragnarök, the boat made of the fingernails of the dead (Naglfar)… this is all known in Iceland, in that lost island.

Serrano: Are you Wagnerian?

Borges: No, I don't like him, because I think he didn't understand much, he made it too romantic, too emphatically. One would say that Wagner didn't understand the Scandinavian… or perhaps I'm the one who doesn't understand Wagner, or a bit of both things. (Laughs)

Serrano: Of the Chinese culture, what things in particular caught your attention? The poetry—?

Borges: I think that Taoism mostly; Chuang-Tzu and Lao-Tse. Chinese poetry too, Eastern poetry in general, Chinese and Japanese poetry… the desire to give everything, for example, a fragrance, to give so many things in so few, necessary words. Synthesis, that's what they've taught us. Such literature and its masterpieces, without large epics which are only a superstition (he's talking about the length). A literature capable of thinking that a man can say everything in only a few casual words, which are not casual at all, of course.

Serrano: And what is the hardest thing to do? To say things in only a few words?

Borges: For example, one reads Confucius' canon and one thinks, "Well, here are some good recipes for good conduct", and then you suddenly realize its author didn't intend to be deliberately rhetorical, to be pathetic. In fact, he discards it, which I believe is something typical of the Chinese and Japanese cultures. The fact of being sober, of being concise, of saying everything with a minimum of words. A minimal emphasis… I think it's very nice. It's a good lesson, especially for me since I tend to be emphatic.

Serrano: Well, you are always fighting with your emphasis. It's a constant struggle.

Borges: It is a constant struggle, and right now you may see I'm being too emphatic, but it can't be helped. (Laughs)

Serrano: Let's talk a little about Spanish culture, which is something so close to us and we are interested in knowing your point of view.

Borges: Well, but we'd need to speak of so many Spanish cultures in so different times. But all in all, and I'll be unorthodox since I'm among friends and I'm allowed to do so, I believe that there's a certain freedom or flow at the beginning of Spanish literature that's lost later in time. For example, let's take something not too primitive, let's look at the case of Cervantes. All that complexity that is known as Cervantes, is a complexity which flows, and one feels there was no effort on his part. But later on, in prodigious men, like Góngora or Quevedo, you find a certain rigidity. And in the case of Gracián, they are overly rigid.

Serrano: You don't like Gracián at all?

Borges: Yes, I don't like him. I think Gracián is something like a caricature of Quevedo. Because in Quevedo, the complexity is carried by an impulse or passion, but in Gracián it is very cold, glacial. Besides, calling the stars, "the chicken of celestial fields", that's unforgivable. I believe Gracián is a German superstition, Schopenhauer admired him a lot, but he probably didn't understand him very much. I would go further though. I think Gracián's thoughts were right, he was very sharp, perhaps a man of genius, but while writing, he felt forced to write everything in an ingenious way, with wordplay or trickery. For example, when he says "Life is a militia against malice", well, that may be true, one could spend his whole life fighting evil, but at the same time, when one reads it in Spanish, not in German translated by Schopenhauer, the first thing that comes to mind is the wordplay, "militia" and "malice", and the intention is lost because of the pun. The trickery actually fights the author[11], because it prevents us from realizing that life is indeed a militia fighting malice, because it's indeed a righteous life, but we are confused by the pun. And that's what happens with Gracián in general. His thoughts were admirable, but when writing, he felt bound to those drawings and symmetries, which are the trademark of the Baroque style, and in this style he was a true master (among the baroque poets), but a master in an unfortunate genre.

Serrano: You feel instant rejection for puns, is that so?

Borges: Yes.

Serrano: I guess you don't like greguerías[12] of Ramón Gómez de la Serna at all.

Borges: Well, no. I think greguerías are superior to puns. I mean, the pun is a form of discourtesy. When I'm speaking with someone, I expect the other to be listening to me, to my ideas. But if he is focusing on my words, it's as if he was only paying attention to the sounds. Like when Gracián says that "Comedies are day-eaters"[13], because comedies are a waste of time. Well, you would not be thinking about comedies but rather in the word "comedy". Conversations can be very a nuisance if there are puns.

Serrano: Of course, because you are getting completely off-track. Puns are frivolous escapes—

Borges: For example, in those verses I found in Gracián, written for a lady called Ana, "Say Ana, are you a target?"[14]. You can't be any more glacial. (Laughs)

Serrano: Fray Luis is another of your favorite authors, isn't he?

Borges: Fray Luis, yes, of course. I remember those verses, that you are probably remembering too: "I to myself would live, / To enjoy the blessings that to Heaven I owe, / Alone, contemplative, / And freely love forgo, / Nor hope, fear, hatred, jealousy e'er know". How terrible that one has to live without love and without hope too. To live without fear, well, that can be stoical… and he writes such a terrible thing so simply. Its structure is not strange, but the idea behind is, "freely love forgo, nor hope, fear, hatred, jealousy". Well, yes, because "hope" is also an uncertainty, those who hope also lay in despair, etc.[15]

Serrano: To make the most out of your visit, I remember that a few weeks ago, some of your comments were published here and were a bit controversial—

Borges: Yes, but those statements were apocryphal—

Serrano: And I believe that as such, you clarified them—

Borges: Yes, I did and I will…

Serrano: Many articles were written, some defending your position, saying that every criticism from Borges is in fact a compliment—

Borges: Well, that's nonsense (he laughs).

Serrano: It's a lovely phrase though.

Borges: Oh, that's nonsense. How could every critique be a compliment (laughs). Every poison served by Borges is nutritious, well, who knows (laughs). Every blow from Borges is actually a caress. No, of course not. It's absurd.

Serrano: So, everything you said about many Spanish writers—

Borges: No, that's false. What I did say is that García Lorca is a minor poet. I don't have to deny it. But I think that anybody can say that García Lorca is a minor poet, and that would not mean an attack to San Juan de la Cruz, for example.

Serrano: Besides, that's your personal opinion.

Borges: Sure, it's my own opinion. I'm not on a mission—

Serrano: Why don't you allow us to hear why you think that García Lorca is a minor poet, which would be much nicer and interesting for all of us.

Borges: Well, because I see him as…—

Serrano: Is it because of his themes?

Borges: No, I think it's my own deficiency. Because I don't understand visual poetry too well, if poetry is merely (inaudible)… For that matter, I think that García Lorca was a professional Andalusian[16], he was very aware of being born in Andalucía. I think that in that sense, Antonio Machado did it better.

Serrano: To you, García Lorca's poetry was too musical—

Borges: I don't know if it was too musical. No, I wouldn't say that. In García Lorca's poetry, I can't find everything I look for in any poetry. However, it would be too difficult to define whatever it is that I'm looking for. What's certain is that García Lorca's poetry doesn't stimulate me. And nothing more.

Serrano: And Machado does provide what you are looking for?

Borges: Both Machados give me whatever I'm looking for. Manuel too. Manuel Machado who was so despised, gives me that too. But I think that they were despised for political reasons only. And Antonio Machado of course, one of the great poets of the Spanish language. Not always, but sometimes he was. And being a great poet for only a few times is good enough, because nobody is a great poet all the time.

Serrano: Here we have a book of poems by Jorge Luis Borges…

Borges: Perhaps you should have looked for a different author and some other text (he laughs).

Serrano: But since we have them, let's make the better of it. For example, here's a poem dedicated to the German language[17], where you begin saying "The Spanish Language is my destiny, "—

Borges: Most certainly.

Serrano: "Francisco de Quevedo's bronze,"

Borges: Yes, I agree with that poem even though I'm the one who wrote it.

Serrano: "But in the marches of the night, / musics more intimate grab me".

Borges: That's true.

Serrano: "Some, came by blood / Shakespeare's voice and scripture".

Borges: Yes, the Bible which I see as an English symbol.

Serrano: "Others by generous hazard".

Borges: Yes, the French language.

Serrano: "But you, sweet German tongue, / I chose and sought alone".

Borges: Yes, that's true. I taught myself German in 1917 and 1918.

Serrano: "Vigils and grammar, / the jungles and declensions, / dictionaries that never get it right, / precisely, brought me near you". Regarding what we spoke about grammar and the right amount—

Borges: Yes, that poem is wrong.

Serrano: It's wrong?

Borges: I mean, I couldn't have written it. It's not so bad. I generously approve.

Serrano: "My nights were full of Virgil, / I said; I could have said, / Hölderling and Angelus Silesius."

Borges: Yes, Angelus Silesius, in the port of (inaudible).

Serrano: "Heine gave me high nightingales; / Goethe tardy love".

Borges: Yes, his Roman Elegies.

Serrano: "Indulgent and mercenary;"

Borges: Yes.

Serrano: "Keller the rose of a hand / in the hand of a dead lover".

Borges: Yes, a Swiss poet, Gottfried Keller.

Serrano: "Who knows not if it be white or red."

Borges: The poems of the man buried alive.

Serrano: "You, tongue of Germany, / are your masterpiece: / love in all your / compound voices, open / vowels, sounds allowing, / Greek hexameter / and rumor of night in the forest. / You were mine. At the limit / of tired years, I spy you / far-off as algebra or moon". It's a typical Borges poem.

Borges: It can't be helped, I can't write poems typical of someone else. (Laughs)

Serrano: Yes, that's logic. Let's read another poem because I think you can tell us a lot of yourself. In Elogio de la Sombra ("In Praise of Darkness") you speak of "Fragments from an Apocryphal Gospel"[18]—

Borges: Well, I think those are essential things. An apocryphal gospel. There, sort of lays my creed.

Serrano: I'm glad for having reached it on pure instinct.

Borges: Maybe that's my essential page, in terms of Ethics and Metaphysics, for example.

Serrano: "Wretched are the poor in spirit, for under the earth they will be as they are on earth".

Borges: Certainly. To imagine that being wretched or unfortunate is a merit, is a mistake. It's nonsense.

Serrano: "Wretched is he who weeps, for he has the miserable habit of weeping".

Borges: Certainly. I believe pondering ill-fortune and tears is nothing but cowardice. Or even demagogic.

Serrano: "Lucky are those who know that suffering is not a crown of heavenly bliss".

Borges: And how suffering could become a crown of glory?

Serrano: "It is not enough to be last in order sometimes to be first".

Borges: No, because otherwise it would be too easy to be the first.

Serrano: "Happy is he who does not insist on being right, for no one is or everyone is".

(Pause)

Serrano: "Happy is he who forgives others and who forgives himself".

Borges: Yes—

Serrano: He may at least be happy.

Borges: Yes, but I don't think one should be overwhelmed by reproaches, to think "I did wrong", because it's a way of insisting in the mistake. If "I did wrong", well, let's forget about it.

Serrano: "Blessed are the meek, for they do not agree to disagree. / Blessed are those who do not hunger for justice, for they know that our fate, for better or worse, is the work of chance, which is past understanding".

Borges: Precisely. How can one ask for justice. Almafuerte said "Ask for justice only, but it would be better not to ask for anything" (he laughs). To ask justice is an excess.

Serrano: "Blessed are the merciful, for their happiness is in the act of mercy and not in the hope of reward".

Borges: Yes, what Shaw wrote in Major Barbara. "I have got rid of the bribe of heaven". Because Heaven would have been a bribe, really.

Serrano: But I think people are always waiting for that reward that never comes.

Borges: Yes, like a certain Scandinavian award that never comes (he laughs).

Serrano: The Nobel Prize that has been given to you for how many years?[19]

Borges: Well, it's been so long it's almost as if they had given it to me.

Serrano: "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they see God". You think a man with an unclean heart will never see God.

Borges: Well, I'm not even sure there's someone who can see God. That's just a literary phrase, let's forget about it. Why don't you scratch it off? (He laughs) It's only a literary phrase, in the saddest meaning of the word.

Serrano: "Blessed are those who suffer persecution for a just cause, for justice matters more to them than their personal destiny".

Borges: That's alright. I agree.

Serrano: Personal destiny is above all. For men, of course.

Borges: For men, certainly.

Serrano: "No one is the salt of the earth; and no one, at some moment in their life, is not".

Borges: Yes, I think that in every life, there's a moment that justifies it, that saves it. In all lives, even the more miserable ones.

Serrano: And here you say, and now you step into deeper and more serious things—

Borges: We'll see.

Serrano: "He who kills for a just cause, or for a cause he believes just, is not guilty". Do you still believe in this?

Borges: Yes, if it was a soldier, for example, he's not to blame. And if it was a brute, he's not to blame either. Only if he believes in whatever law that makes him—

Serrano: So the long or short hand of Justice is just, even if it's unjust in the end.

Borges: Yes, it may be.

Serrano: "The acts of men are worthy of neither fire nor heaven".

Borges: Yes, besides it's absurd. Suppose I live to be 80 years old. How could that be rewarded with an eternity of Heaven or Hell? It's a disproportion. In this very moment, on Earth, we could be rewarded or punished just as much.

Serrano: Maestro, do you believe in Hell?

Borges: Well, many times on Earth, we experience that feeling of Hell, and sometimes the feeling of paradise. I believe that every man's memory is between those two moments. You probably have felt as if you were in Hell, and sometimes in Heaven. I mean, bliss and misfortune are not ignored by us. What does happen is that Heaven is rare and Hell is more common.

Serrano: "Do not hate your enemy, for if you do, you are in some way his slave. Your hate will never be greater than your peace".

Borges: It's selfish advice.

Serrano: You are not being generous in this last line, you are working for yourself.

Borges: Of course. Yes, a very selfish phrase.

Serrano: "If your right hand should offend you, forgive it; you are your body and you are your soul and it is hard if not impossible to fix the boundary between them…"

Borges: Yes, contrary to the notion of some people that if your right hand should offend you, you should cut it off…

Serrano: And now we speak of Truth. You write, "Do not make too much of the cult of truth; there is no man who at the end of a day has not lied, rightly, numerous times."

Borges: Evidently. If you are introduced to someone, you say "Glad to meet you", who knows if you are or will be glad. Besides, it's better to lie.

Serrano: Lying is like a self-preservation instinct—

Borges: Yes, I think so too. To insist in speaking the truth at all times is a pedantry, ethical pedantry.

Serrano: It would be impossible to live on truth alone.

Borges: Coexistence would be impossible. Being truthful at all times would be an exercise of selfishness and vanity.

Serrano: "I do not speak of revenge nor of forgiveness; oblivion is the only revenge and the only forgiveness".

Borges: Yes, I wrote a poem where I speak of this, the difficulty in the art of oblivion. Of course, it's hard. All in all, one must try to forget certain things. Besides, in the long run, one manages to forget.

Serrano: "Happy are the poor without bitterness and the rich without pride. / Happy are the loved and the lovers and those who can do without love".

Borges: Yes, but it's certainly better to love or be loved than to do without love. I'm afraid I don't agree with this South American author (he laughs). Besides, he's already made too many mistakes in one single page.

Serrano: And here's something very nice, which I agree with. "The door, not the man, is the one that chooses".

Borges: It seems like a great line, but it's not. It's OK, though. Like a memorable but hollow phrase. But it looks good.

Serrano: It's destiny that actually chooses—

Borges: Yes, but "door" is better, don't you think? The metaphor was properly chosen. If I wrote "the road", it wouldn't sound good.

Part 4[]

Serrano: We have gone through some of your philosophical beliefs, Maestro. Let's continue with a little more of your personal life—

Borges: Of course, but please, don't call me maestro. I am nobody's maestro.

Serrano: Well, but to me, you are a Maestro, you're a master to us all.

Borges: Please, don't. Call me Borges.

Serrano: I'll call you Borges, with pleasure. Borges, to you, what is hate?

Borges: I don't know, I don't feel hate.

Serrano: You've never felt hate?

Borges: Well, if I think of two dictators of my country, but I try not to think of them. Of Rosas and the other[20]. That might be a form of hate, to try to forget, but it's better than abundant vituperations.

Serrano: Do you think think hate is corrosive?

Borges: Yes, feeling hate is to destroy oneself. It turns against you when you hate, which is better not to hate.

Serrano: And loving is to enrich oneself?

Borges: Yes, it's always enriching. Loving more than being loved or not. The moment one feels love, it's something, isn't it?

Serrano: Do you like being loved?

Borges: It would be awe-inspiring if I said no. But in reality, I like feeling loved.

Serrano: I know you are a shy man—

Borges: No, but, it would sound better, as I am speaking publicly, if I said I disliked being loved. But I do like it.

Serrano: It would be normal if you liked it.

Borges: Sure; and why would being normal be a bad thing. Besides, if I lied, everybody would notice I'm lying.

Serrano: You've always talked with disdain about the desire to have power, about the pride of who is in control.

Borges: Yes, however, I've never had that desire of power. Like Marcus Aurelius said, not a master, not a slave. We shouldn't be neither. A master is a sort of a slave if you think about it as he has to be always worried about others.

Serrano: For you, Borges, what is life?

Borges: I'd say it is an interesting adventure, and we have a compromise with this adventure. And that we will die undertaking this adventure, happily or ill fortunately.

Serrano: In 1919, you came to this country; you lived some time in Barcelona—

Borges: Yes, but I remember better the nights of Café Colonial, of Cansinos Assens…

Serrano: Later you were in Palmas de Mallorca for a year. You lived in Valdemosa, near the Cell of Chopin. In a time where tourism was almost inexistent—

Borges: Yes, there were no tourists back then. I was the first tourist, a sad honor though. (Laughs)

Serrano: You wrote some books in Spain which weren’t published—

Borges: It was only reasonable not to publish them.

Serrano: One was titled Salmos Rojos ("Red Psalms"), you were referring to the October Revolution.

Borges: Yes, precisely. But during those times, being a communist meant something else. It meant a longing of universal fraternity. It meant Walt Whitman, a little, or pacifism. But now it has a different meaning. Now it's a form of Russian Imperialism, a rancor between certain people. Yes, I was a communist back then.

Serrano: There was another book, titled Los Naipes del Tahúr ("The Cards of the Gambler", "tahúr" can also mean a gambler who's very good at cards or one who cheats at cards), where your Baroque influence could be seen.

Borges: Yes, but I don't remember absolutely anything from that book. I've managed to cleanse myself from that memory.

Serrano: Both books vanished without a trace—

Borges: Yes, only the title remained, which is not so bad. Besides, two Arabic words[21], it doesn't sound so bad.

Serrano: One of your stories was rejected in the journal La Esfera ("The Sphere")[22]; I don’t know if this happened to you more than once.

Borges: I'm not sure if it happened more than once, but it surely didn't happen in the magazine La Esfera, rather in others. (Laughs) But there's nothing special about it…

Serrano: You had literary gatherings with Rafael Cansinos Assens—

Borges: Yes, in the Café Colonial, known as the café of the red sofas, of the big mirrors. It was a remarkable time. We arrived at midnight, a quarter hour before midnight, actually, and we stayed there till dawn. And Cansinos Assens proposed a topic, for example, the metaphor, the rhyme, the plot, and we would discuss it during the whole night. And he forbade us from mentioning any writers. He didn't want us to attack anybody. He meant for the get-together to be something Platonic… and we kept going till dawn. And then we would walk Cansinos back to his place, in the Morelía street, close to the viaduct… Talking about literature all night long. I haven't seen such passion ever since, except in Buenos Aires, in the literary gatherings of Macedonio Fernández, but there, the discussions were rather metaphysical. Cansinos was a man of exceptional courtesy. Sometimes there would be up to 20 men, and then, if he saw a new face, he would ask where they came from. Then he would talk to that person about their region, and then the conversation would move to the general topics.

When I was leaving Europe, and the time came to say good-bye to Cansinos was like if I was saying good-bye to all of the libraries of Europe. It seemed as though he had read every book. I think he spoke 17 languages. He gave me the impression that he WAS every library, that he WAS every language. A whole life dedicated to literature. I remember a poem he wrote dedicated to the sea. I remember thinking, "What a beautiful poem, Rafael", he insisted us in calling him Rafael. And he said, "Yes, I hope to see it sometime", with an accent of Andalucía he never let go. He had never seen the sea. The sea inside his mind was enough for him. Like Coleridge and his Rime of the Ancient Mariner. An extraordinary poem, yet he had never seen the sea.

Serrano: You then traveled to Sevilla, Andalucía; you encountered the Ultraist movement.

Borges: Exactly. Adriano del Valle, Isaac del Vando Villar, Luis Mosquera; later in Madrid, Gerardo Diego…

Serrano: Pedro Garfias—

Borges: Yes, but Pedro Garfias was from Andalucía, from Osuna.

Serrano: You met Juan Ramón (Jiménez) too…

Borges: No, I never met him, I don't know why. It's quite strange that I didn't know him. I met him years later, in Buenos Aires, when he gave some conferences.

Serrano: And you began collaborating with the magazines of the time, Hélices (plural of "Helix", could be either the 3D curve or the blades of an airplane engine) , Cervantes, Grecia, Ultra, Cosmópolis…

Borges: Yes. The names the magazines had back then!

Serrano: It was a different time, different titles…

Borges: Nevertheless, what was so beautiful to see was so many young men with a great passion for literature. Nowadays you don’t see that. What's the present passion, really? There is more of a passion towards politics or personal gain, economical gain. But a passion for philosophy, like I encountered in Buenos Aires, in the literary meetings of Macedonio Fernandez, the passion for literature like in the case of Cansinos Assens gatherings, I don't know if that collective interest for philosophy and literature happens today. Certainly, individually it may happen, but I am not sure if collectively.

Serrano: You went into literature without ever thinking about your financial reward.

Borges: No, I never thought about that.

Serrano: You stayed away from those financial concerns…

Borges: Well, for a time I stayed away because I had my family and I didn't need to. My father told me that I needed to do was: write a lot, correct a lot, tear down almost everything, and not to hurry to get published. That's why when I published my first book in 1923, Fervor of Buenos Aires, it was really the third one I wrote, and I never thought of taking it to the bookstores, nor to send it to other writers, nor the newspapers, I only distributed among friends. And now I realize that thousands of people have read it. It's very odd. It's as if with the passing of time, one finds himself surrounded by followers, by friends, and that is very heartwarming.

Serrano: And then a fervor for Borges starts, thanks to that book, which is the first but it's actually the third.

Borges: Well, fortunately is the first one, because the previous two were certainly embarrassing.

Serrano: You return to Buenos Aires after spending so many years in Europe with a great deal of enthusiasm and love for your city… as far as saying that your absence was merely an illusion, that you never left Buenos Aires.

Borges: Well, that's an exaggeration. It's nonsense. I don't know how I could say that.

Serrano: Perhaps it was out of cordiality…

Borges: "The years I spent in Europe are illusory; I've always been and always will be in Buenos Aires". Yes, I think it's simply pathetic. I don't think it was psychologically accurate. How could I be in Buenos Aires if I was reading Arabian Nights, which happens in Baghdad?

Serrano: Your first book was well received, specially by the young generation, the avant-garde movement…

Borges: Yes, but just as soon as I published that book, I came to Spain. I spent a year here and when I went back to Buenos Aires, I found out that the book had found many readers which I didn't expect.

Serrano: And the young Argentinian writers had seen in your book a way to join the new movements.

Borges: Yes, certainly. But these days I don't care about the movements. I mean, the schools of literature are purely (inaudible) of the critic.

Serrano: You returned to Paris, to Madrid, to Mallorca, Sevilla, Granada—

Borges: I don't know if I returned to so many places, but I have visited some of them twice, yes. I know very little of Paris, I don't have that Argentinian cult of Paris. In return, I think very affectionately of the south of France. But Paris… not so much. Of course, it's my own deficiency. I should feel Paris in some other way, but unfortunately, I don't.

Serrano: Perhaps because you found more things you could relate to in other places rather than Paris.

Borges: Well, sure. I think of Geneva with great love, of Edinburgh…

Serrano: Then it comes Luna de enfrente ("Opposite moon").

Borges: Let's forget that one.

Serrano: Cuadernos de San Martín ("Notes on San Martín")

Borges: Let's forget about that one too.

Serrano: We've forgotten this poetic trilogy. Inquisiciones ("Inquisitions").

Borges: Yes, that could be forgotten too. Practice, in the style of Saavedra Fajardo, Quevedo.

Serrano: In those inquisitions, there were articles on Quevedo, Unamuno, Cansinos, González Lanuza… El Tamaño de mi Esperanza ("The Size of My Hope"), published in 1926.

Borges: Yes, a dreadful book.

Serrano: Historia Universal de la Infamia ("A Universal History of Infamy").

Borges: Well, this book was my first attempt at short stories, but with a little of shyness. I introduced those stories as if they were real but they were in fact, pure fiction. It was like a game. In reality, those were the first stories I wrote, like a test, an experiment. The exercise helped me to write real stories later on.

Serrano: El Jardín de los Senderos que se Bifurcan ("The Garden of Forking Paths").

Borges: Yes, I think that's a pretty nice book. The story of a labyrinth.

Serrano: In 1938 you lost your father and in Christmas of the same year, you suffered from an accident which almost kills you.

Borges: Yes, if you feel my head, you can see the documentation of the accident.

Serrano: How did it happen?

Borges: Going up the stairs I hit some blinds someone had left open. I fought a case of sepsis and I was almost dying though I didn't think of death at the time. I tell this in one of my stories entitled El Sur ("The South"). The beginning of the story refers to my accident, and, well, the ending is fantastic.

Serrano: During those days you had high-fevers, you were delirious…

Borges: Yes, whole nights of insomnia, of nightmares, of feeling very miserable.

Serrano: You went under surgery and during your recovery time, you wrote that first fantastic tale.

Borges: Yes.

Serrano: In that moment, you start discovering yourself. Borges starts finding Borges…

Borges: Well, I realized that I could write fantastic tales. I proved it. I proved that I had that aptitude. And I took advantage of it ever since. For better or worse. And right now, I have a tale in my mind that could be the best of them all. But I will not reveal anything.

Serrano: You shouldn’t reveal anything until it's written.

Borges: Yes, if one reveals things too early in the process, one never writes them.

Serrano: Why did you work as a librarian? Because of your love for books? To have an occupation? For an extra income of money?

Borges: It is actually a combination of all those. In addition I love being inside a library.

Serrano: It was a modest library, in a small neighborhood…

Borges: Yes, but even so, a modest library can exceed the capabilities of any reader. I've read many great authors while working there. For example, I discovered Léon Bloy, I found Claudel. I didn't know them. There were many works by Hugo which I didn't know and I read them there.

Serrano: The Garden of Forking Paths was presented for the National Prize of Literature. Another forgettable author won the prize. Argentina was outraged—

Borges: Not Argentina's outrage but the indignation of my close friends…

Serrano: So you received a tribute in the magazine Sur ("South"), a special number where many writers collaborated.

Borges: Yes, many writers. Also a friend of mine, Eduardo Mallea, and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle I think.

Serrano: And Sábato.

Borges: Yes, Sábato too, who was a young writer at the time.

Serrano: Then you were the recipient of the Prize of Honor of the Argentine Society of Writers.

Borges: Yes. Enrique Amorim, an Uruguayan writer, created that prize so that I could receive an award that year. He invented the prize and many other authors received it later in time. It was devised against the National Prize.

Serrano: It was the anti-National Prize.

Borges: Exactly.

Serrano: In 1944, one of your best-known collection is published: Ficciones ("Fictions"). Peronism comes to power; you speak in conferences for Argentina and Uruguay…

Borges: Yes, I'd like to forget about those years.

Serrano: You leave your position in the library, or you were indirectly dismissed, however you'd like to put it.

Borges: Well, they assigned me to be an inspector of birds an eggs in the municipal market, and one way or another, I understood they wanted me to resign (he laughs). My competence in terms of eggs and birds was rather null.

Serrano: You declared yourself unfit for this new position.

Borges: Yes, I found this way of honoring a writer with such extraordinary position a little odd. (Laughs) It was one of the jokes of the time.

Serrano: You founded the magazine Anales of Buenos Aires ("Buenos Aires Annals"), where a short-story by the unknown writer Julio Cortázar were to be published.

Borges: Yes, the first text written by Cortázar ever published. And there we published a number dedicated to Juan Ramón Jiménez. Juan Ramón Jimenez had come to Buenos Aires, to give a few lectures asked by Ms. Sara de Ortiz Basualdo who was the chief editor of the Annals.

Serrano: You put together an anthology of the best police stories.

Borges: Yes, that was a very influential book, and also an anthology of the best fantastic tales.

Serrano: What do you think of police stories? Of detective novels.

Borges: I'm a bit tired of the genre. They're like if they could be mass-produced. But there are remarkable stories, like the ones by Chesterton, by Poe, by Wilkie Collins. I think it's a genre that tends to be mechanic.

Serrano: In 1949 is published the book which earns you worldwide recognition: El Aleph ("The Aleph"), 14 stories, and later on you added 4 more. In total 18 stories which show your beauty and intelligence.

Borges: Well, thank you very much.

Serrano: Were mathematical thinking and metaphysical profundity are fused together—

Borges: Do you believe that's my best book?

Serrano: Well it is the book that has made you most popular, and has been most read.

Borges: Yes. Probably. Perhaps it was because the word "aleph" sounds nice and it's written with "ph"? (He laughs) That could be one of the reasons.

Serrano: I wouldn't know, you studied so much of this subject, from the Kabbalah—

Borges: The importance of a good title.

Serrano: In 1950, you are elected President of the Argentine Society of Writers. During your lectures, the police is keeping an eye on you.

Borges: Yes, and later that society was shut down but you know who, because we didn't want to put the portrait of a certain couple on display.

Serrano: You became Professor of English Literature at the Argentine Association of English Culture. You became interested in Anglo-Saxon literature—

Borges: Yes, I also was Professor of English and American Literature at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters of the University of Buenos Aires, which made me feel very pleased because I greatly enjoy being a teacher. I like teaching. I love teaching more than I like giving conferences. During a class, people are more serious; during a conference, people are just there to watch who's speaking. In a class, people pay more attention to the subject, which is more interesting than the tie or the looks of who's speaking.

Serrano: During those years, you kept writing and Los Orilleros ("The Hoodlums"), El Paraíso de los Creyentes ("The Paradise of Believers")…

Borges: Yes, those were two films scripts we wrote with Bioy Casares.

Serrano: And there's a very interesting book of gaucho poetry that you published in Mexico.

Borges: Yes, in that book it's gathered the whole body and soul of gauchesque poetry. From the poems of Bartolomé Hidalgo up to… well, everything is included in that book. There's a unpublished poem by Hernández, Los Tres Gauchos Orientales ("The Three Eastern Gauchos") by Lussich; rare texts you don't come by very easily. However it was released with plenty of errata because it was published in Mexico, where naturally…

Serrano: This gaucho poetry, do you think it's an epic poetry?

Borges: Well, in some way, it is epic, especially in Ascasubi, in Hernández I'm not so sure. In the case of Hernández, I don't know if the story of a deserter who later becomes a murderer and a fugitive can be epic. It's something else, a novel in any case, but it's remarkable nonetheless. I think considering it an epic was a fabrication of Lugones. Hernández would surely be surprised by that notion. I think it's more of a sort of protest against the levy.

Serrano: From a literary point of view, you obviously like Martín Fierro, no?

Borges: Yes.

Serrano: What do you like about it?

Borges: It has a certain sobriety and uprightness to it. For example, it's seems impossible to write about the gaucho without including a description of the Pampa, of the plain. However, in Martín Fierro there's no such description, yet we feel the plain, and I think that's remarkable.

- From a ranch, Cruz and Fierrorounded up a string of horses;

they drove them on ahead

like people who know how,

and soon, without being noticed,

crossed over the frontier.

After they crossed it,

one clear morning,

Cruz told him to look back

at the last settlement;[23]

there you have the plain. "After they crossed it, / one clear morning, / Cruz told him to look back / at the last settlement"; that's much more effective than the descriptions of other authors.

Serrano: In that sense, it is a narrator like yours, of preciseness, of conciseness—

Borges: Yes, I think is. I think its descriptions are more remarkable than the descriptions we may find in other remarkable book, Don Segundo Sombra. In Don Segundo Sombra, the author leaves the story to describe that, for example, on the left there is a mountain, on the right, a ranch. In Martín Fierro, everything flows. The descriptions are not explicit but they are somehow given.

Serrano: It contrasts with all the other books of gauchesque poetry because where everything is described, even excessively.

Borges: Besides, the peasant does not see the landscape as a landscape. I mean, the landscape is an idea of the educated man. In Martín Fierro there are no landscape descriptions because it's understood the narrator is a gaucho (a peasant). The peasant cannot see the landscape. If a peasant looks at the sky it is to tell whether rain is coming his way or not, but not out of aesthetic joy. That would be completely untrue.

Serrano: In 1956, you receive the National Prize of Literature, meaning everything eventually comes; you are given the chair of English Literature at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters of the University of Buenos Aires.

Borges: Two friends of mine had also applied for that chair, they asked to be the jury to select the candidate, and they chose me. They turned down their applications and chose me instead.

Serrano: And you are given a honorary degree in the University of Cuyo, but your blindness was worsening…

Borges: Yes, the first doctorate honoris causa I've ever received, and later I received others, in Oxford, now I'll receive the degree in Santiago de Chile. I've also received titles in Colombia…

Serrano: Now let’s talk about someone who was there, especially during the times when you were forbidden to write and read due to your worsening blindness…

Borges: My mother.

Serrano: Your mother was your friend and, perhaps, the closest person to you.